Be Nice. Project

Giving away an unused, free movie pass on my college campus proved more difficult than I expected in 2008. I was met with annoyance and suspicion, ultimately failing in my good deed.

This was the impetus of the Be Nice. Project. – my response to this “last straw” after two years of poorly adjusting to a Northeast urban city after relocating from a Big Ten Midwestern college town.

Overview

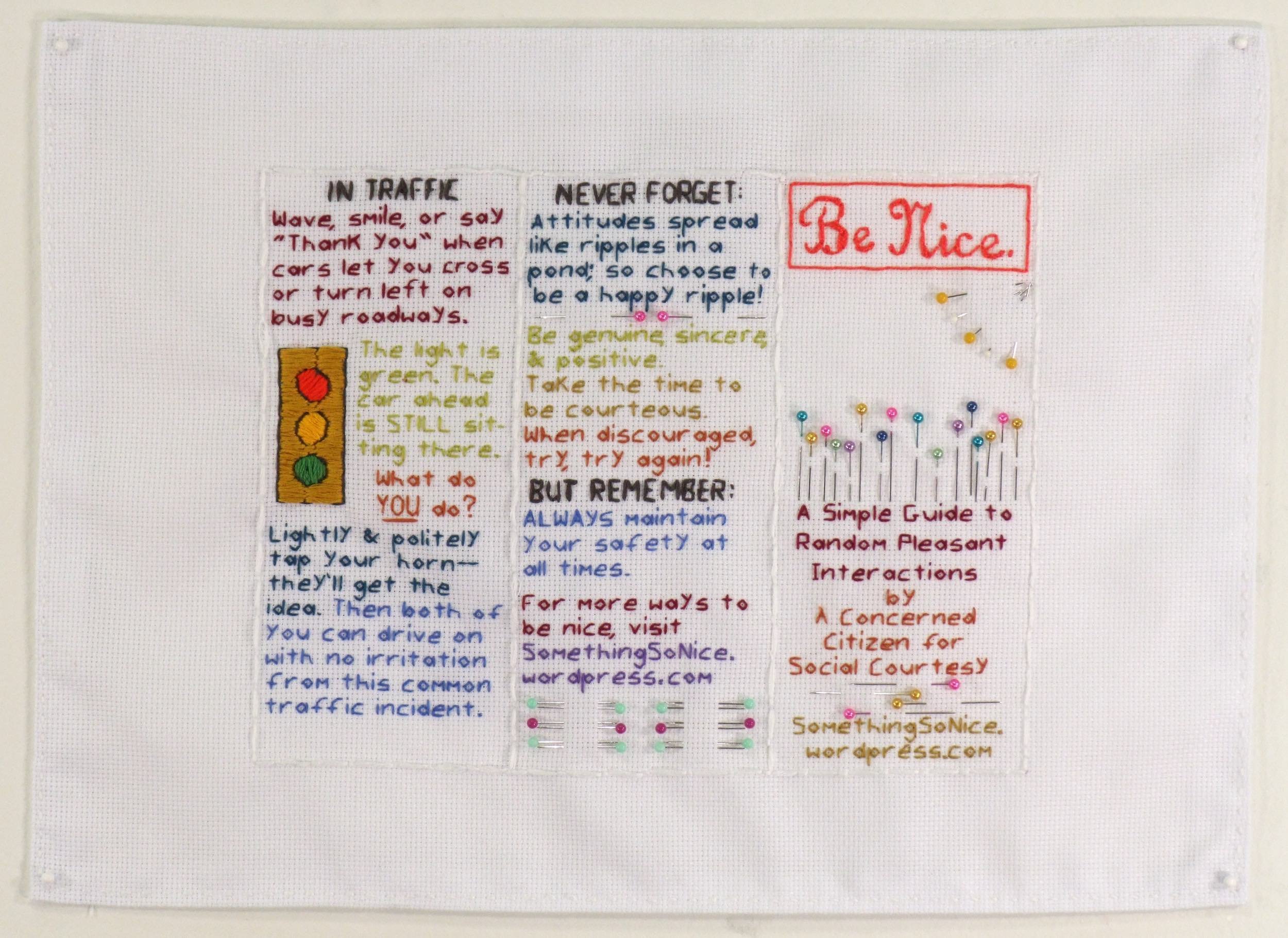

The initial piece was conceived as an instructional pamphlet on manners and politeness. It was hand embroidered and created to scale for the sole purpose of reproduction into a trifold paper brochure. The brochure was distributed free of charge throughout various communities and cities – from doctor offices and coffee shops to travel plazas and business entrances.

A blog was created to complement the brochure and expand upon its message. Initially using WordPress blog URL, the BeNiceProject.com domain was later purchased as the project expanded.

Through 2010, two postcards and a final quad-fold pamphlet were each created in a similar fashion: hand-embroidered and reproduced as paper ephemera to be freely distributed. The blog was actively maintained until 2013 and was available online through 2023.

Insights

Falling into the realm of service aesthetics – in which the intention was sincere and with an element of public service – the methods chosen for the work were by nature wide-reaching rather than confined to art galleries. Understood to be dismissed, forgotten, or impactful, the work operated as a means to encourage self-reflection and opening one up to the benefits of kindness, politeness, and positivity.

During this time, Facebook and blogs were growing in popularity and iPhones were only a few years old. We saw the revival of craft in fine art, The Happiness Project by Gretchen Rubin, and the reinvigoration of the Emily Post Institute with new generational staff.

Project Highlights

‘Foot in Mouth’ syndrome and the ‘Curse of Considerate Clarification’ was “Freshly Pressed” on WordPress, relating in 75 comments. 2010

For $200, Jason Mewes and Kevin Smith, hosts of the podcast Jay and Silent Bob Get Jobs, did a four-minute, live read of a paid ad promoting the Be Nice. Project Kickstarter. May 26, 2011

Jay and Silent Bob Get Jobs was part of the Smodcast Podcast Network and S.I.R. (Smodco Internet Radio), which includes podcasts such as Smodcast, Hollywood Babble-On, and Tell ‘Em Steve-Dave! Owned by filmmaker Kevin Smith, these podcasts rose to popularity during the nascency of the podcasting industry.

Successfully completed a Kickstarter campaign to print the quad-fold pamphlet at a 181% funding rate with 52 backers. 2010-2011

Featured in Mr. X Stitch podcast. 2011

Showcased cross-stitched pieces completed by a Brooklyn classroom of 85 seventh graders each displaying a lesson they were learning. 2011

Featured on a digital billboard as part of the Billboard Art Project. 2012

Included in the coffee table book Humor In Craft by Brigitte Martin. 2012

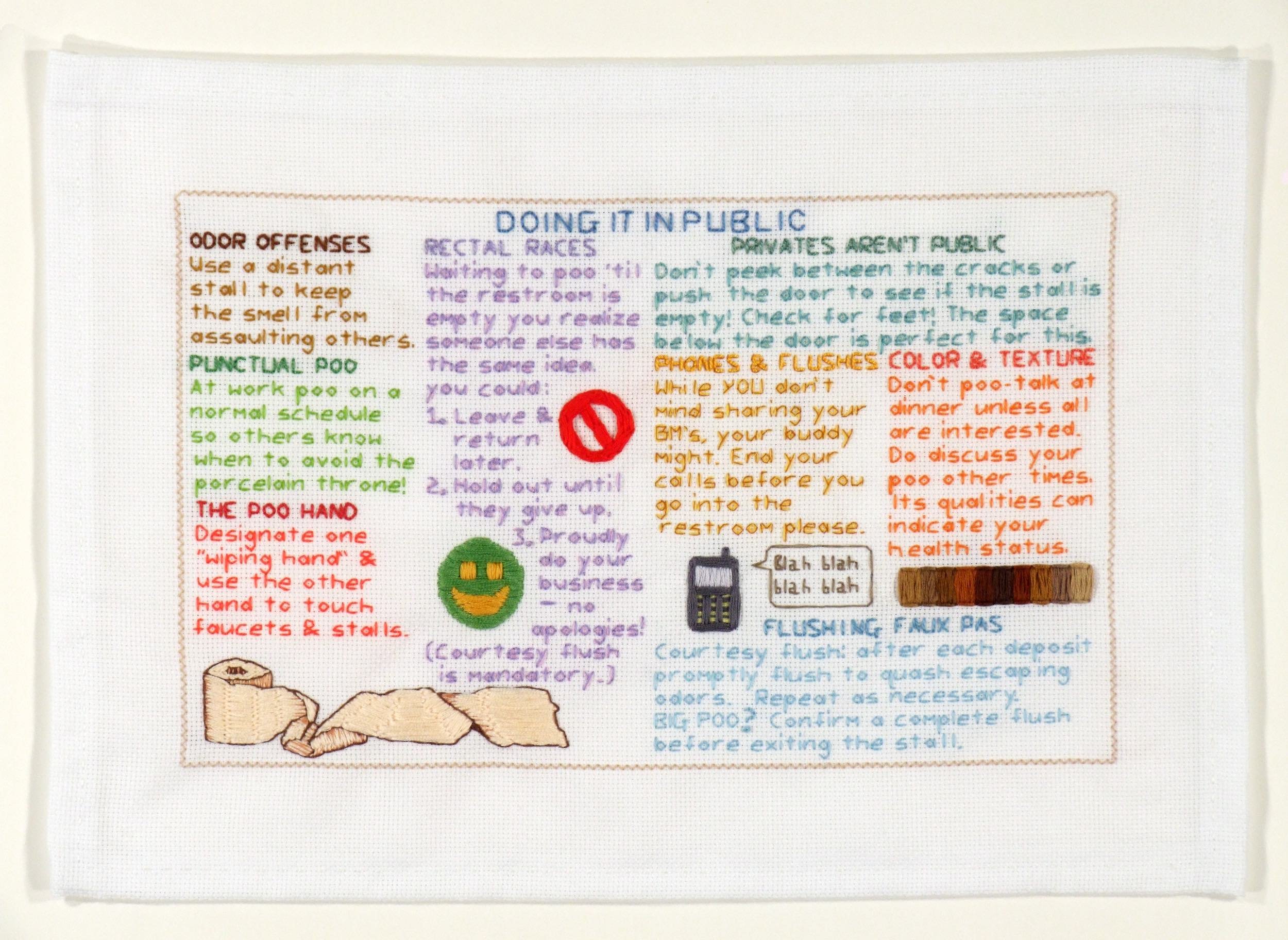

View of Be Nice. Guide to Farting and Pooping brochure (inside, outside, and folded). Unfolded dimensions: 8.5 x 14 inches

View of Be Nice. brochure (inside, outside, and folded views). Unfolded dimensions: 8.5 x 11 inches

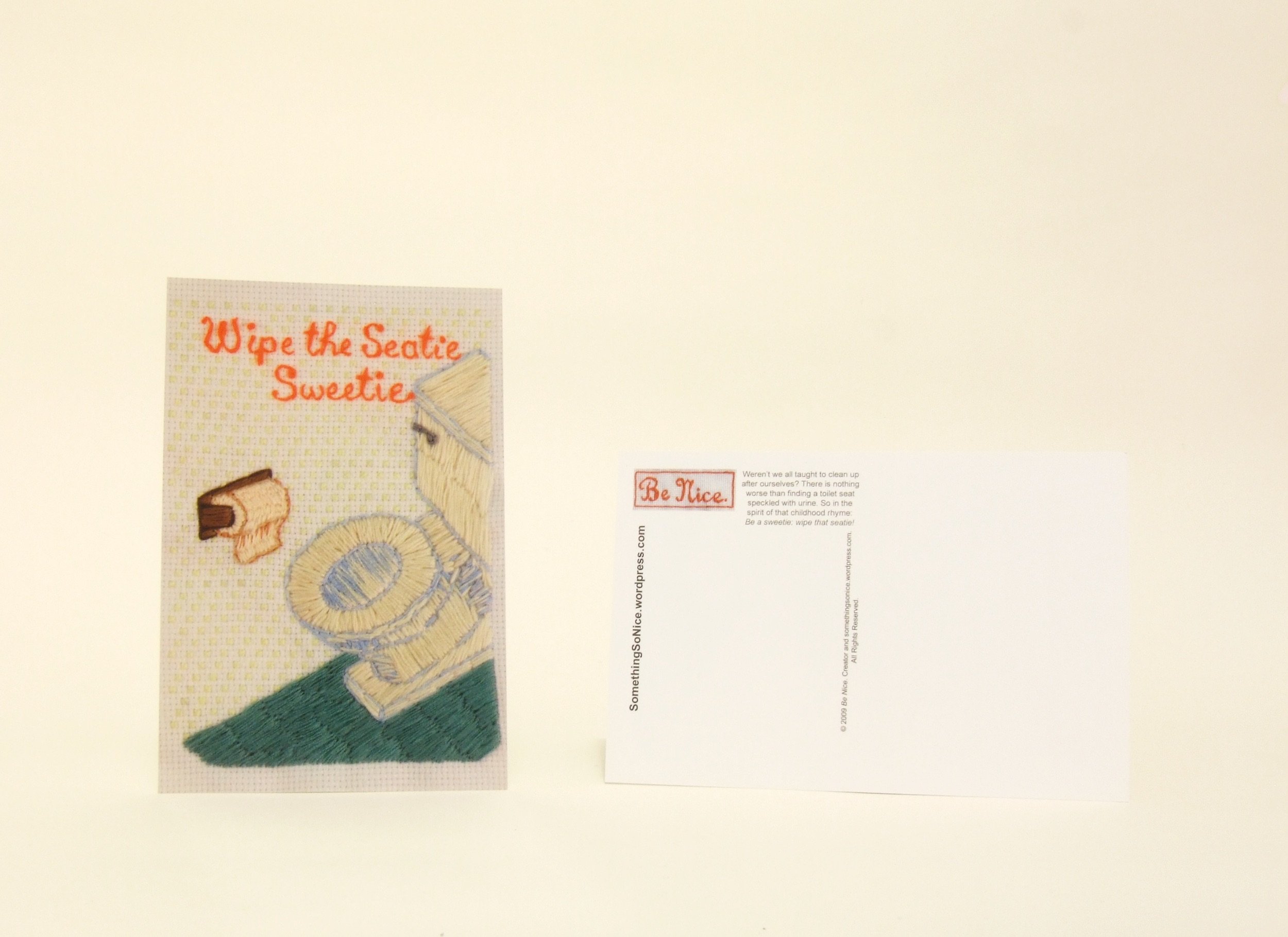

Front and back view of Wipe the Seatie Sweetie postcard. 4 x 6 inches.

Front and back view of SOAP + H2O = Nice. postcard. 4 x 6 inches.

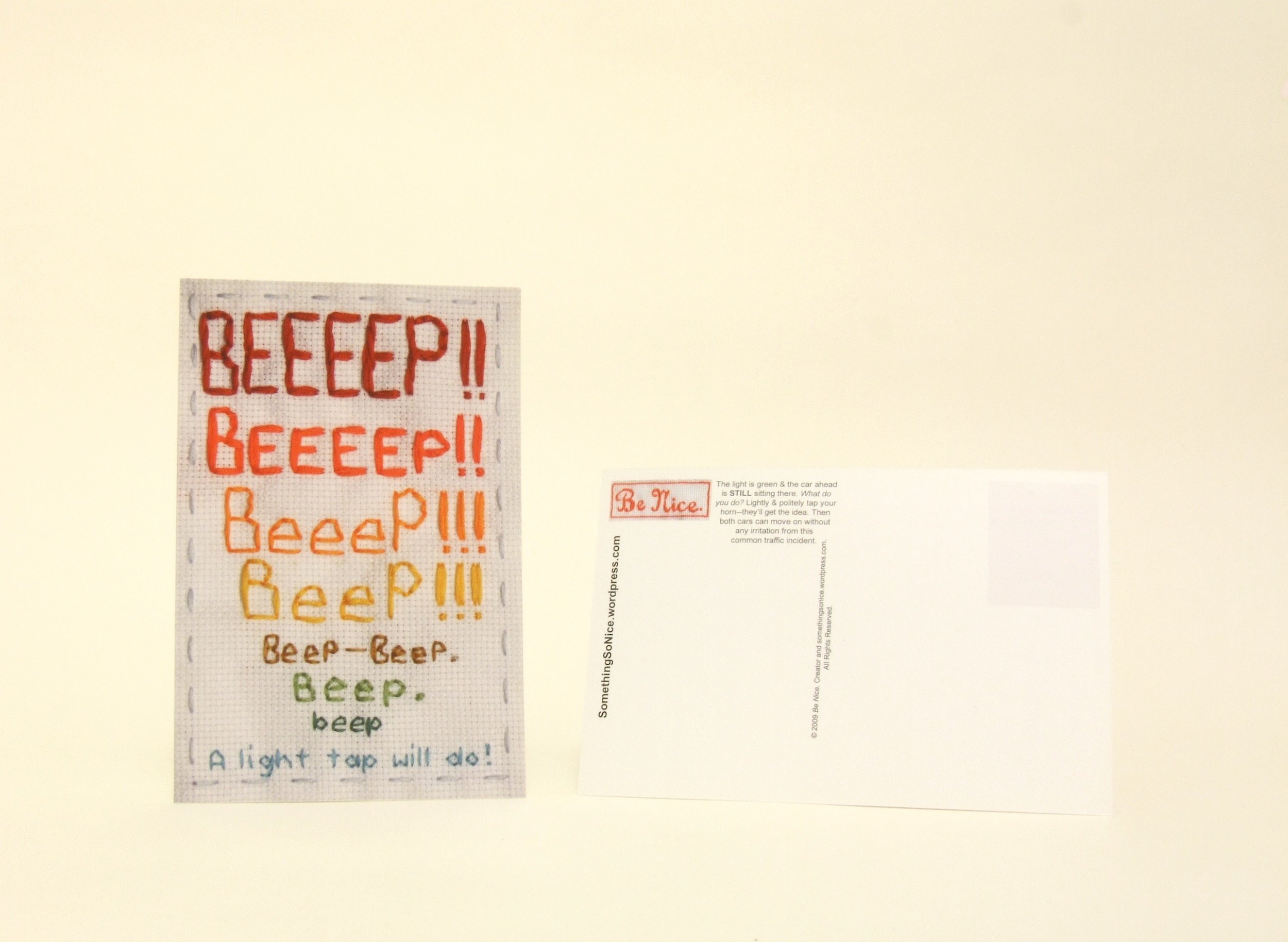

Front and back view of Beep! postcard. 4 x 6 inches.

View of blog in exhibition. 2009

Screenshot of Be Nice. Project blog

Screenshot of Be Nice. Project blog

View of digital composition for the Salem, Oregon Billboard Art Project show. May 2012. Image courtesy of the Billboard Art Project

Be Nice. (Left panel). Hand embroidery and straight pins on cross-stitch fabric. 12.5 x 17.25 inches. 2008

Be Nice. (Right panel). Hand embroidery and straight pins on cross-stitch fabric. 12.5 x 17.25 inches. 2008

Beep! Hand embroidery on cross-stitch fabric. 10.75 x 10.75 inches. 2008

SOAP + H2O = Nice. Hand embroidery on cross-stitch fabric. 10.25 x 10.25 inches. 2009. Private collection

Wipe the Seatie Sweetie. Hand embroidery on cross-stitch fabric. 10.5 x 10.5 inches. 2009. Private collection

Be Nice. Guide to Farting and Pooping. Outside panel. (When printed into four-panel accordion fold brochure: far right section is the front of the pamphlet, far left section is the back of the pamphlet, and the inside section is the inner pamphlet.) Hand embroidery on cross-stitch fabric. 12.5 x 18 inches. 2010

Be Nice. Guide to Farting and Pooping. Inside panel. (When printed into four-panel accordion fold brochure this whole panel is on the inside of the pamphlet.) Hand embroidery on cross-stitch fabric. 12.5 x 18 inches. 2010

Yellow: Mellow, Brown: Down. Hand embroidery, padding, and cloth on cloth. 14 x 12 inches. 2014. Private collection

Press

Griffin, Amy. "Art Above: Billboard Art Project to come to Albany." Times Union, June 28, 2012; page 9.

Dahlmann, Greg. "The Billboard Art Project." All Over Albany (blog), June 19, 2012.

Martin, Brigitte. Humor in Craft. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, 2012; pages 89 and 225.

Lerner, Liz Clancy. “Be Nice. Please.” All Over Albany (blog), March 10, 2011.

Chalmers, Jamie and Bridget Franckowiak. “Episode 15: Stitching n KitKat.” Stitching n Junk (podcast), January 31, 2011.

Franckowiak, Bridget. “Beefranck’s Emporium -- The Be Nice Project.” Mr X Stitch (blog), January 17, 2011.

Artist Statement, 2010

Mass-produced media and social networking are coupled with the matriarchal sampler to draw a response that fluctuates between sincerity and cynicism. The plasticity of reactions to the "Be Nice." project indicates individual relationships with our society: defensive, suspicious, receptive, symbiotic, and so on. While irony and subversion come standard in contemporary imagery and communication, here sincerity is subversive.

The "Be Nice." project includes works that are embroidered by hand specifically for duplication into brochures and postcards. Each piece is reproduced at a one-to-one scale with its paper counterpart. These ephemera are consistently distributed throughout the U.S. and abroad. An additional component of the project is a regularly updated blog at www.BeNiceProject.com, which analyzes the complexity of our social and cultural landscape. Facebook and Twitter are also used to mobilize the project socially, involving a dedicated following of readers who then voluntarily distribute the materials.